Seated cross-legged on a floral carpet, white trainers peeking out beneath black abaya, they are as curious about me as I am about them. Both university students in Madinah are excited to see non-Muslim women; to them, it’s a sign their country is evolving and creating new opportunities.

Like everyone I’ve met since arriving in Saudi Arabia, it’s another rewarding connection that provides a window into a country few might consider visiting. Saudi Arabia began issuing non-pilgrimage tourist visas in 2019, as part of its ‘Vision 2030’ to diversify its economy. However, with restrictions on freedom of expression and my own preconceptions, visiting wasn’t a straightforward decision.

In Riyadh, traffic is at a standstill as 10-lane arteries are clogged with beeping cars. We’ve just left Diriyah, known as Saudi Arabia’s birthplace, where in 1744, a pivotal socio-religious pact was signed laying the foundations for the early Saudi state and Wahhabism, the dominant religious ideology. Crumbling mud-brick buildings wither beneath monstrous tower cranes constructing one of Saudi’s ‘giga-projects’, which includes the 170kilometer-long city called The Line and are attracting controversy for their environmental impact and displacement of communities. It’s a visual tension of preserving the past, while racing towards the future—Diriyah is also 2030’s designated Capital of Arab Culture.

I ask Noura about her award-winning business, HiHomes. Much like our visit, HiHomes offers visitors a glimpse into Saudi homes, an initiative she is proud of, especially for the connections it creates.

Abdullah gestures us into his majlis, a carpeted room with low, soft seats and mud walls decorated with geometric patterns. Noura pours amber-colored cardamom coffee from a dallah, an Arabic coffee pot, into tiny cups, and offers sweet Saudi-grown anbara dates. Abdullah holds court, asking everyone who they are, while generously sharing his own family’s stories. Once the formalities are over, Noura’s cheerful mother welcomes us into the main home, wafting the sweet, smoky scent of oud from a golden incense burner.

Leaning over, Abdullah adds that “the only way to see Saudi Arabia is through a Saudi home”. Noura attributes her success to her supportive family and government grants, but she’s downplaying her own entrepreneurial skills that started with only friends and family as hosts, but has expanded to over 200 experiences in under five years. Bidding farewell with kisses to the cheeks and bags of dates, it is easy to see why Noura cherishes these connections.

This warmth continues in the rural, conservative town of Ha’il, 600 kilometers from Riyadh and where international tourists are a rarity. We draw curious, friendly, stares from men and women, along with shouts of ‘Welcome!’ and requests for selfies “because my friends will never believe me.”

Yet, the picture remains complex. The 2022 Personal Status Law, originally designed to end discrimination against women, still requires women to obtain male permission for marriage. Labor protections don’t extend to migrant workers, who make up 42 percent of the population, despite UN recommendations.

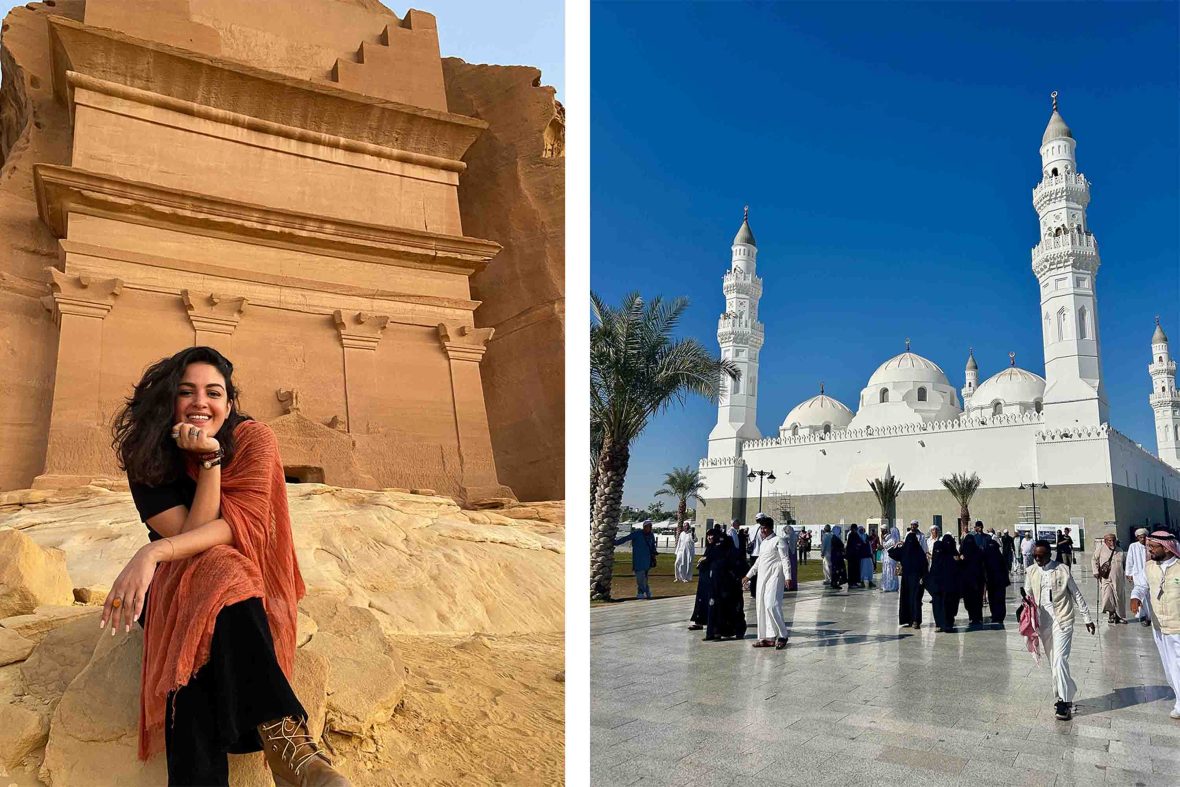

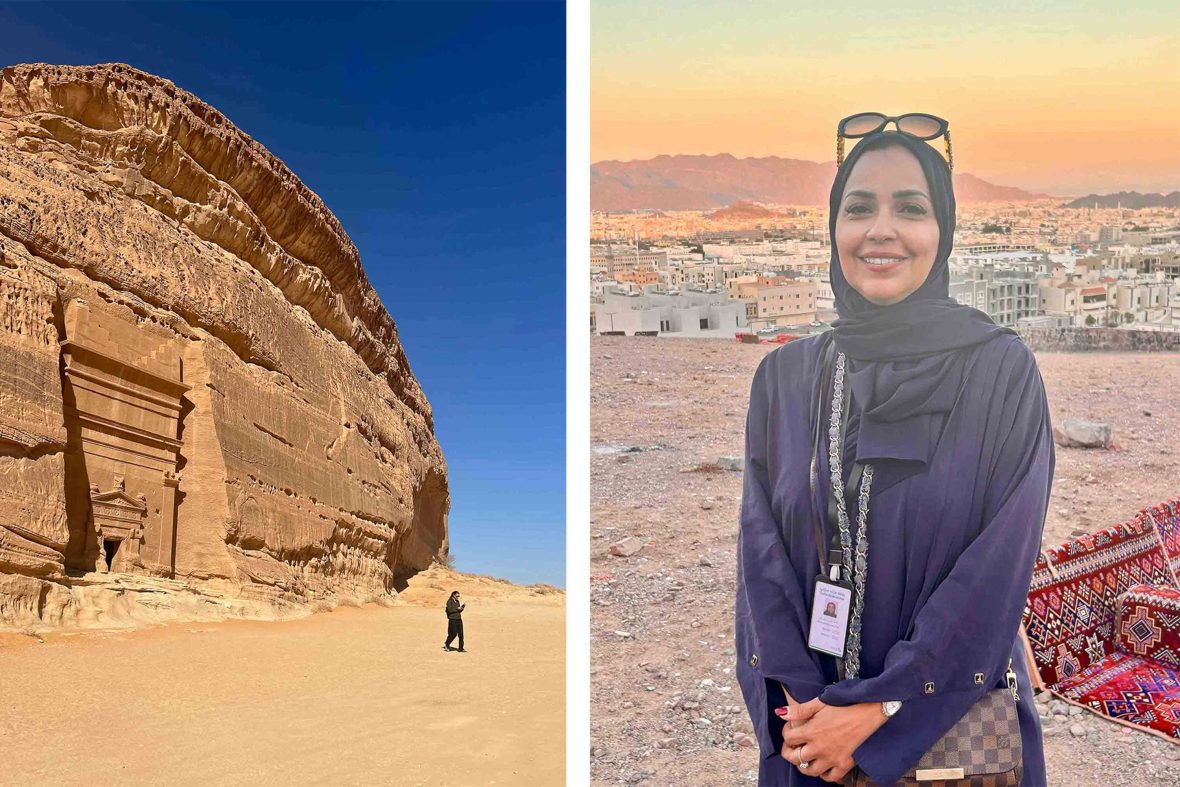

At this UNESCO World Heritage Site, most rawee (storytellers, rather than guides) are female, but our rawee is Muhammad who played among the tombs as a child. He explains how the Nabataeans, an ancient Arab civilization known for their ability to trade through the harsh desert environment, transported frankincense and myrrh through Hegra to Petra in Jordan over 2,000 years ago.

He shows us how tomb designs of eagles and ancient scripts provide insights into Nabataean society including how women enjoyed greater freedoms and owned property and businesses. One well-preserved tomb enabled experts to create a facial reconstruction of a prominent 40-year old woman named Hinat. Gazing into her eyes at the visitor center, I wonder whether this visual representation of ancient female society resonates with the conversations Saudi women are having about freedom and identity today.

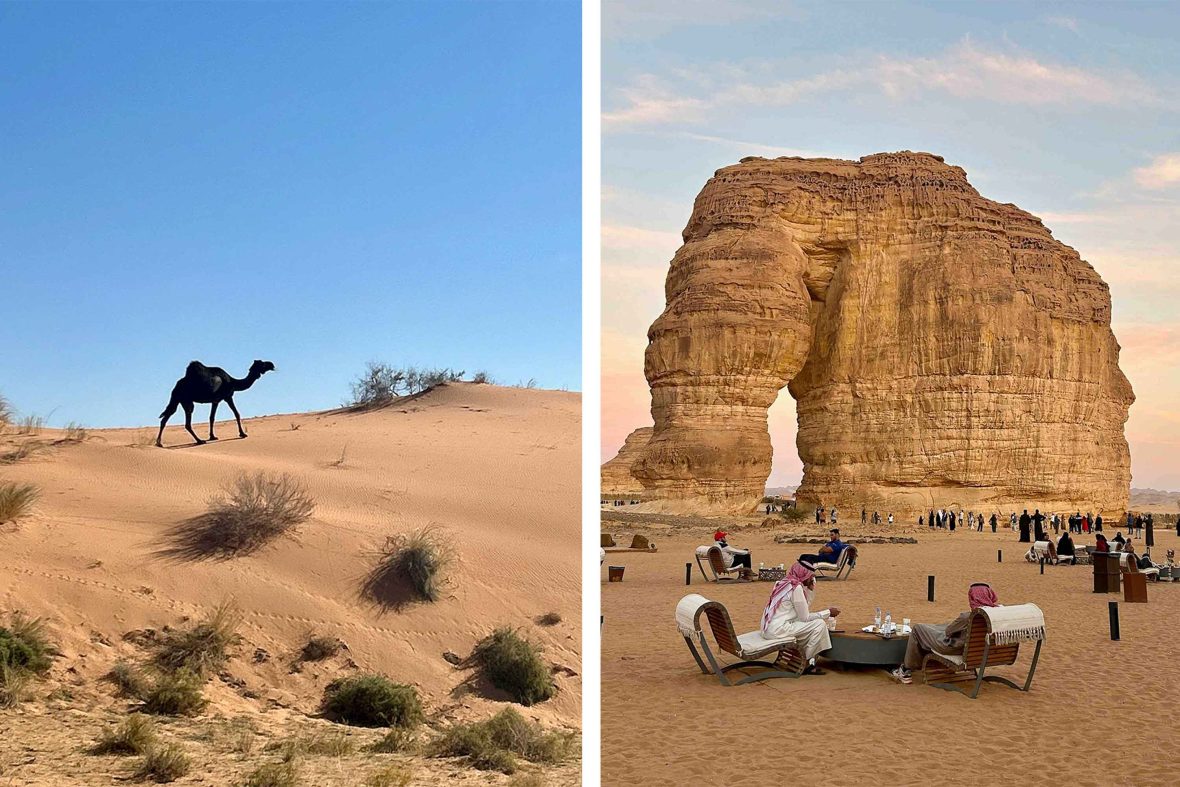

Rugs are laid out at our Bedouin picnic spot and the Adhan echoes through the city as streetlights flicker to life. As we dip sharaik, sweet flatbread, into yogurt and baharat spice mix, our conversation turns to the word ‘choice’—how many Saudi women decide who to marry or divorce, and whether to wear a hijab or Western-style clothes. Listening to their stories, I become more aware of the assumptions I arrived with, and how this country is often viewed through a narrow lens.

Many migrants work on major national projects, including infrastructure for the 2034 World Cup, but we also met poorly-paid female workers with limited rights; for many, especially those without privilege, there remains a barrier to freedom. At times, conversations glossed over certain realities, and even in 2025, LGBTQ+ rights are too sensitive to discuss openly.

It’s often said travel broadens perspectives and deepens understanding, and this journey has certainly been mentally exhilarating. Many of my misconceptions have given way to a more nuanced view, where kindness and hospitality are deeply rooted, but at the same time, some concerns have been reinforced.

We discuss the pace of societal change, particularly the visible dominance of men in some spaces and the occasional absence of women. Sara explains that, in general, Saudi women are shy and feel more comfortable having a husband or brother with them. She says, “it’s going to take us a year or two before the women can stand out and be the center of attention.”

As this is Intrepid’s first women’s expedition in Saudi Arabia, it feels like a privilege witnessing this moment of change. “Tourism seems to be the number one sector for giving women new opportunities,” says Sara, “so if you’re a chef you can create a cooking school.” I ask if she believes that tourism can bring meaningful, long-term change to Saudi women if nurtured thoughtfully. She doesn’t hesitate. “100 percent yes,” she replies. “I really hope this opens doors for more people to see Saudi, and being on a women’s expedition makes a big difference.”